UNPICKING THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY: # 3

Decoding the archery. One in the eye for Harold - perhaps - but if so, what type of bow shot it and who exactly were the archers in Duke William's army?

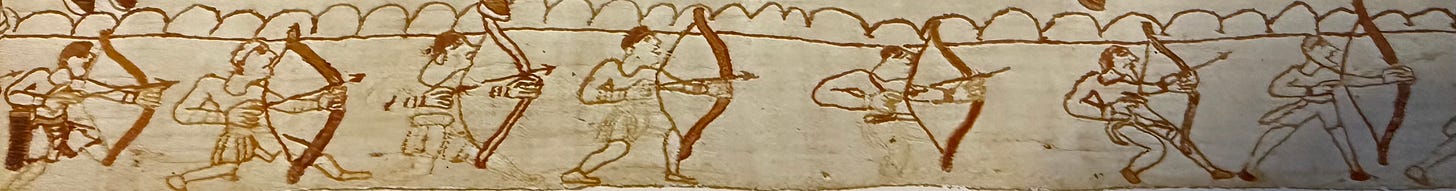

The Bayeux Tapestry features 36 bowmen— thirty-four Norman infantry archers and one solitary Saxon archer; plus a single Norman horse-archer. Given the general artistic excellence and detail elsewhere in the tapestry, you might think it a simple thing for such a talented atelier of embroiderers to have rendered the shape of a bow accurately. But no; the images of bows are childishly poor and conspicuously inconsistent. It is as if they were trying to portray something that had been described to them, but that they had never seen.

This could very well be the case if what we are talking about are recurved composite bows - and if so, it means that William’s archer corps were an elite and prestigious fighting unit of crack troops, not a rag-bag of villainous villeins.

I will come to that idea in the next article in this series (because I do think that is what they are) but first, for those who consider such a notion too outlandishly exotic, let’s examine the case for them being wooden ‘short bows’, which, to be fair, they may well be.

SHORT BOW vs LONG BOW

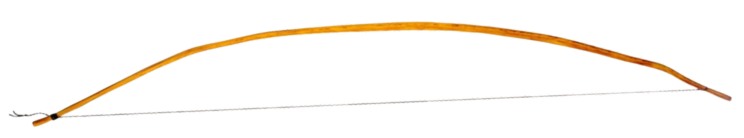

With regard to a simple wooden bow (composite bows are different), the mechanical distinction between a longbow (roughly 1.8 - 2 metres) and a short bow (roughly 1.2 - 1.7 metres)1 is that a longer stave allows you to draw the string back further before the thing snaps. The further the string is drawn, the more energy is stored and the bow shoots with greater force; having greater range and impact.

In the case of the English longbow of the 100-Years-War, that meant drawing to the ear. In the instance of a short bow, that meant drawing only to the centre of the chest, which of course is what we see on the Tapestry. In fact, this repeated representation of the short draw is the main driver for the ‘wooden short bow’ argument.

Although the quartet of archers in the main panel (image at top of this page) are armed with unmistakably short bows, the bows in the margins appear overly large. It may be that this is an artistic choice. Throughout the Tapestry, the images in the margins serve as allegory and commentary to the main narrative in the central panel, so these outsize bows may simply be telling us just how important a role the archers played in this invasion force; a commentary on their military value.

Rather than taking the inconsistent form of the bows as our main clue, it is the manner of their use that suggests a short bow - and that short draw is shown throughout.

Short bows are definitely a thing. In other parts of the world, we have stacks of evidence for functioning wooden short bows. They were, for instance, a primary hunting weapon for many Native American tribes. When stalking at close range, the short draw is an advantage because, requiring less movement to operate, there is less chance of spooking the game. Not as powerful as a longbow, but at 50lb - 60lbs, the draw weight of these bows has sufficient wallop to bring down a deer at close range.

A chest draw also makes it significantly easier to shoot on the move, whether walking or even at a slow jog. We see the archers doing this on the Tapestry - they are an agile mobile force, quite different from the stake-bound bowmen at Agincourt. Bringing a powerful longbow to full draw behind the ear can only be accomplished by a standing archer. Circumstantially, the argument for short wooden bows seems compelling. They might be something a low-status levy could muster with and they could be useful enough for short range skirmishing on the battlefield.

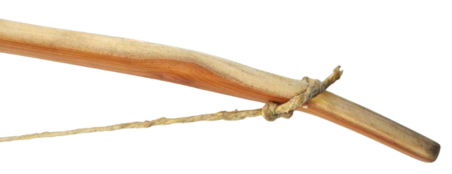

THE WATERFORD BOW

Although there is no definitive archaeological evidence for the short-bow surviving in England, Viking, or pre-Conquest Norman contexts, there are examples from the 1100s in Ireland. Among several fragments of bows discovered at Waterford, was one complete bow that was stable enough to be fully excavated. Made from yew, it measures 1.26 metres (4 feet 1.6 inches) from tip to tip. It is a bow of substantial girth and unlikely to have been for a child. The assumption is that shorter bows like this, used by ordinary folk for hunting, co-existed with longer bows that packed a heavier punch for military use. Test shooting with a replica of the Waterford Bow, beautifully made by Jeremy Spencer, who followed the exact dimensions, has indicated a bow with a 60 lb draw weight when using a short chest draw2. Unearthed alongside the bow was an intact arrow, measuring 60cm (23.6inches), including its bodkin head.

EVIDENCE IN ART

Until the discovery of the Waterford Bows in the 1980s, the existence of early medieval short bows was inferred entirely from their appearances in art - a primary example of which is the Bayeux Tapestry, and we can hardly cite the work itself as evidence of its own veracity.

However there is a 12th-century manuscript illustration, depicting the Martyrdom of St Edmund in 869, which strongly supports the idea of such bows. The Passio Sancto Eadmundi tells the story of St Edmund, King of East Anglia3. Not only do his executioners use identifiably short bows and a chest draw, their bows also show the distinctive style of nock (string groove) that we see on both the Waterford bow and the Bayeux Tapestry.

The bow extends for a notable length beyond the nock. This feature offers no mechanical advantage to the bow’s performance, though it may function to give extra leverage when stringing. While a bit of a mystery, it serves as a useful identifier.

On the Tapestry, a short bow with this style of nock is clearly depicted in use by the figure of the Saxon bowman. He appears in the main panel, dwarfed alongside some burly housecarls. The distorted proportions of his size, together with the fact that only one Saxon archer is shown, probably signals that the Saxon army contained very few archers and that they were considered of low status.

For our Saxon, a simple fyrdman, I would conclude 100% that he is using a wooden short bow in the style of the Waterford bow - a type of bow that was familiar to the Canterbury needlewomen. It is possible that the Norman bows were of a similar pattern but I don’t think so.

THE VIKING CONNECTION

The Normans (Norsemen) were of Viking descent. In 911 they began their settlement of the lower Seine valley in Northern France. They were led by their chieftain, Rollo. Duke William was Rollo’s great-great-great-grandson. There had been more than a century of assimilation by the time of William’s invasion, but it is not unreasonable to assume a continuity of certain weapon types.

There have been longbows since the Neolithic period. The longbow wasn’t a new concept that suddenly emerged in the later middle ages. The Vikings certainly had longbows. The most complete example is the magnificent Hedeby bow from Denmark, which measures 1.91 metres (6’ 2”) and has been dated to between the 9th and 11th centuries.

It has been calculated that the Hedeby bow would have a draw weight of around 100 lbs. That is a significant military advantage over the 50 - 60lbs we might expect from a short bow.

So could the confusingly rendered Norman bows on the tapestry have represented Viking style longbows? Yes - it is possible and equally possible that there were a mixture of types. However, if this were the case, surely there would have been little problem in illustrating them clearly.

More significantly, any potential power advantage of a longer bow is completely nullified by that short chest draw. So the question now becomes - would a 50-60lb short bow have an adequate martial application on the battlefield?

THE SWINGING DOORS OF THE SHIELD WALL

The effectiveness of battlefield archery depends on what you want it to achieve. A 60 lb bow with a short draw (the draw length is a big factor in this regard) probably has a maximum range of no more than 165 metres (180 yards) - but, unless it hits you in the eye (!) - it would be of little consequence at that distance. Its effective range (ie being able to deliver significant thump) is far closer.

Even at extreme close range, a bow of this draw weight is unlikely to have penetrative power against either shields or hauberks. However, that does no disqualify its usefulness. A constant barrage of hard, stinging hits is more than a mere annoyance. Even hardened warriors would need to defend themselves against the wearying effects of such an onslaught.

The Tapestry shows the shields of the Saxon shield wall bristling with arrows like a prickle of porcupines. In great number they would make the shield awkward to use. More importantly, defending against such a shower of shafts, forces the shield wall to keep its doors closed; that is keeping the shields held squarely in front.

This matters because it limits the range that spears can be thrown at the enemy. Of course it is possible to throw a spear and still keep your shield directly in front of you but to impart any meaningful power, you need to rotate the body. start with your left shoulder forward and then swing from the hips with all your might to bring the right should forward and the right arm fully extended in front of you - it opens the door; your shield pivots to one side.

It may seem counter-intuitive but, during the throwing war phase, it was beneficial to the attackers to force the defenders to keep the doors of their shield wall shut. This limited the range at which the front line could hurl their spears.

Norman cavalry, men-at-arms and archers worked together for a combined forces attack. It wasn’t a staged offensive, with an arrowstorm from distant archers followed by the cavalry - they attacked together. In this way the archers were instrumental in hampering the Saxon’s ability to repel the missile cavalry, who were able to ride in close and throw their spears over the front row and into the ranks.

It is questionable whether, with short-draw, short-bows, the archers could have any effect with high, arcing shots, which is not to say that they didn’t at times shoot with a modest amount of elevation.

ARROW IN THE EYE – OR NOT?

Was the image of the arrow piercing King Harold’s eye present on the Tapestry at the time of its creation? Possibly not. Some believe the arrow was a later addition by conservators during the 1842 restoration, seeking to conform the visual record to what had by then become the popular story.

Earlier 18th-century sketches of the scene show the same figure holding a spear above his head, not an arrow in his eye. The hand position works for either scenario. So there is a question – was the spear unpicked and replaced with an arrow? Perhaps current conservation and modern analysis will give us a definitive answer.

There is another issue. The embroidered inscription telling us the scene shows King Harold being killed - ‘Haroldus Rex Interfectus Est’ - is predominantly framing the man being hacked down by a Norman knight, immediately to the right of the figure with the arrow in the eye. This is more likely to be Harold and being cut down by a Norman knight aligns closely with the contemporary account in the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio.

The Carmen (The Song of the Battle of Hastings) was written in 1067 and has been attributed to Guy of Amiens. It is the closest account we have to the date of the battle. I shall be looking at it closely in the next essay in this series, together with the account from William of Poitiers, who wrote his report within five years or so of the battle4.

Henry of Huntingdon

The main textual support for the ‘arrow in the eye’ story comes from Henry of Huntingdon, who wrote his Historia Anglorum some 60 years after the battle. It is conceivable that he had access to a primary source, now lost to use, but equally probable that he made the whole thing up. He is known for his penchant for dramatic licence5. The incident is not cited by either William of Poitiers or in the Carmen. Huntingdon wrote,

“a shower of arrows fell round King Harold, and he himself was pierced in the eye.”

It was also Huntingdon who wrote,

Duke William commanded his bowmen not to aim their arrows directly at the enemy, but to shoot them in the air, that their cloud might spread darkness over the enemy’s ranks; this occasioned great loss to the English.”

I think this too is false. He may have thought it helped to embellish the arrow-in -the -eye story but overhead volleys are not a necessary condition of being shot in the eye. The Norman bowmen were fighting uphill, so that would deliver quite enough lift. If the case is for short-draw short-bows, then Hollywood style arrowstorms from above are not plausible.

THE CASE FOR THE COMPOSITE BOW

Although I remain open to the idea that the Norman bows at Hastings were wooden short-bows, I believe that there are some equally compelling clues to suggest that they were high-end, recurved composite bows. There are plenty of extremely wiggly ones that tease the idea. That they are poorly depicted could be explained by imagining that the artist has only seen wooden short bows but has had these new-fangled recurve, composite bows described. The result is a confused muddle.

If you’d like to read my ‘case for the composite bow’ and my take on the Bayeux horse archer, be sure to subscribe so that you receive a notification, when it is available.

1.8 - 2 metres = roughly 6ft - 6ft 5in / 1.2 - 1.7 metres = roughly 4ft - 5ft 6in.

More details from these tests can be seen here: https://www.warbowwales.com/_files/ugd/1dca4f_4217cb1aec084c1e98378d2c4bd65491.pdf

According to legend, Edmund was martyred, by being shot with arrows, for protesting his Christian faith to Viking invaders. Incidentally, this home-grown martyr remained the primary patron saint of England, until he was jostled from position by the Cappadocian St. George in the 15th century.

William of Poitiers wrote Gesta Willelmi Ducis Normannorum et Regis Anglorum (Deeds of William, Duke of the Normans and King of the English) around 1071.

He is responsible for the story of King Cnut talking to the waves and for the story of Henry I dying as a result of eating a surfeit of lampreys. Both tales are considered untrue, written to add dramatic colour to his ‘history’.

Another fine piece. Thanks for sharing with us.

No trouble at all. The three posts on the Bayeux Tapestry so far have been really informative and I've enjoyed all three.

Looking forward to your thoughts on other aspects.