OUT IN THE COLD

April 18, 1943:

Lieutenant Hermann Ritter, a 51-year-old, Austrian naval officer, reluctantly in the service of Nazi Germany, was exhausted, hungry and bone-achingly cold.

Six days previously he, and his small command, had set out from their base at Hansa Bugt, situated on one of those frozen tendrils of land that fringe the north-east coast of Greenland, and headed south.

They had crossed treacherous ice fields and made their way along the trappers’ trails that snaked around the feathering of frozen fjords. At times these trails crossed the fjords directly. It was a perilous gamble to sledge over the frozen sea ice, but they did it.

Under Ritter’s command were four German soldiers. Two travelled on a sledge1 hauled by a team of Greenland dogs, whilst the other two slogged on foot. A second sledge, heavily laden with supplies, was driven by a Danish hunter called Marius Jensen. By reputation he was an exceptional dog musher. He was 31-years-old; 20 years younger than Ritter.

Ritter and Jensen travelled together, but it would have been too dangerous to add the weight of a passenger to the sledge; only the driver could stand on the runners. There was no telling when a crack in the ice would plunge it into the Arctic waters beneath. Hermann Ritter, despite being the older man, had to journey alongside on foot. He was no stranger to polar travel but this was an especially gruelling journey.

His heavy wooden skis had weighty steel edges to bite into the ice when crossing frozen fjords. When traversing snow-covered hills, he strapped strips of sealskin to the undersides. These allowed the skis to slide forward but bristled against the snow to prevent sliding backward. Where the snow had drifted, he had to shoulder his skis and tramp, lifting his ice-heavy boots as high as he could, like a soldier marching on the spot, to plough through the snow. It was all grunting, unrelenting, hard work.

It was a far cry from the life Ritter had known years earlier, when the Arctic was a place of adventure rather than war.

At this time of year, daytime temperatures could rise to between -13°C and -7°C (8°F to 20°F) but at night they dropped to around -25°C (-13°F). However, in the Arctic, April is known for its merciless winds, causing the wind chill factor to plummet to -40°C (-40°F). Adding to their discomfort was 20 hours of daylight, making it hard for the body to rest.

Trappers’ huts, basic wooden cabins dotted every 12 miles or so along the coastal trails, offered some respite from the constant glare, the savage cold and the lacerating wind, but if supplies weren’t to run out before they got to the next main station, travellers could stay only briefly.

Ritter’s patrol reached a trapper’s hut at Myggebugten on April 18th, where they sheltered from a storm, and rested the dogs.

THE SWITCH

The next day, April 19th, Ritter commanded his four soldiers to head for Ella Island, where there were reports of an Allied weather station. Their orders were to destroy it. The trapper, Marius Jensen, had drawn a map for them the previous evening.

Ritter’s plan was to stay behind with Jensen and make further reconnaissance in the area. He saluted the men as they set off and then stepped back into the cabin to ready himself for his mission. Hermann Ritter and Marius Jensen were now alone.

Outside Jensen was finishing up harnessing his dog team. In preparation for their scouting trip, Ritter had propped his skis, ski-poles and heavy bolt-action rifle (a Mauser Karabiner 98k) against the sledge, and then gone back inside.

From within the hut, Ritter heard the distinctive, heart-stopping, click-clack / clack-click of the rifle bolt - a round was now in the chamber. He perhaps assumed a polar bear had been sighted, but when he appeared at the door, he found himself staring down the barrel of his own rifle. Marius Jensen said simply:

“Now you are my prisoner”

He probably said it in German and the emphasis would almost certainly have been on the word ‘my’ because, until that moment, Jensen had technically been Ritter’s prisoner. It was a switch.

Marius Jensen, was not just an arctic hunter and expert dog musher; he was a member of Denmark’s North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol and he had been captured by Ritter and his men several weeks earlier, on March 26.

But why were Jensen and Ritter in Greenland in the first place?

THE WEATHER WAR

With overwhelming force, German forces occupied Denmark, on April 9, 1940. Despite continued, courageous resistance from the population, the government had little choice other than to co-operate. While the Danish government was under German rule, Greenland's link to Danish sovereignty was effectively severed.

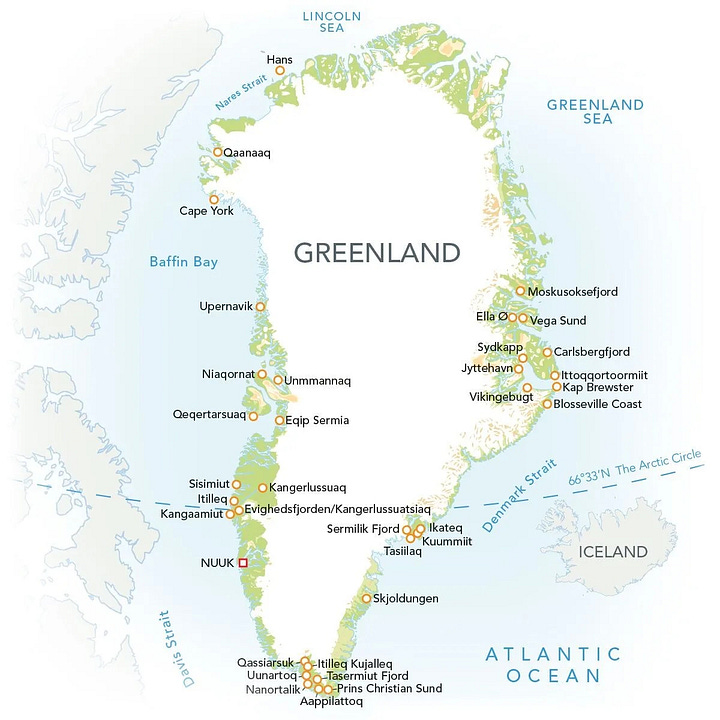

After a brief period of diplomatic manoeuvrings, Eske Brun, one of two Danish governors, who had run the colony up until then, declared autonomous control of the entire island. He set up headquarters in Nuuk and declared support for the Allied cause. The other governor, Aksel Svane, took himself off to Washington as a liaison.

In 1941, the United States assumed temporary security responsibility for the island and set up vital airbases.

Greenland was a large and strategically important landmass2. It was an unsinkable aircraft carrier, situated between North America and Britain, that allowed short-distance combat planes to cross the Atlantic for service in Europe. Greenland’s capital Nuuk sits almost exactly halfway between Washington, DC and Copenhagen.

Aside from its value as a refuelling base, Greenland was crucial for the gathering of weather intelligence. Before satellites, weather patterns sweeping into Europe could be predicted from weather stations in Greenland and radioed to both Washington and London.

This was critical information for planning both air and naval operations. The North East of the island provided the most relevant data. North Atlantic weather generally moves from West to East; whoever controlled the Greenland coast had a crystal ball for the weather that would hit Europe 24 to 48 hours later.

Obviously, these meteorological reports were of equal interest to the Germans.

THE SLEDGE PATROL

Eske Brun, the governor, was all too aware of this and so, in 1941, he set up the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol. He initially recruited 15 men - 10 Danes, 1 Norwegian, and 4 native Greenlanders. All were trappers and hunters; they all knew the trails and the terrain. Marius Jensen was among them. They operated in pairs and relied entirely on dog sledges.

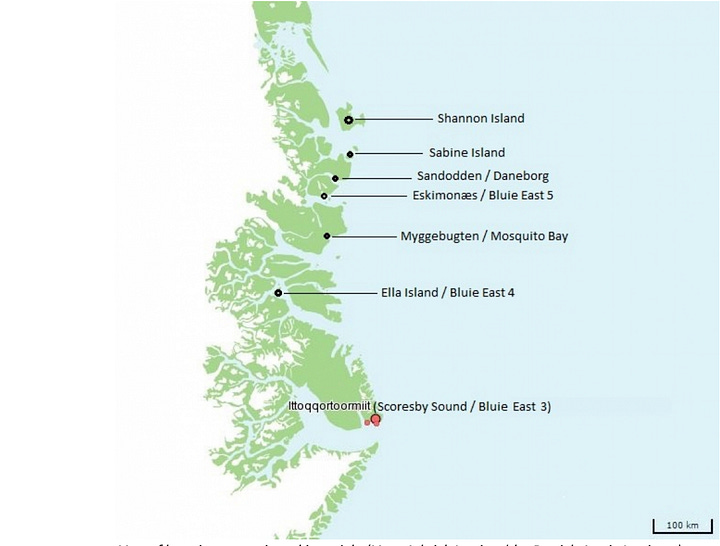

Their task was to patrol 700 miles of uninhabited coastline in search of German weather stations; a beat that stretched from the far north as far down as Scoresbysund. Below there, the island was ‘relatively’ more populated and the locals could keep an eye out for any German activity.

The North East Greenland coast is fringed with vast fjords, encased with fingers of rocky upland. For most of the year the crags are snow-covered and the fjords are sealed with sea ice. During a single ‘spring patrol’, a two-man team would typically cover over 2,500 miles (4,000 km) of travel, weaving in and out of the fjords to ensure no Nazi weather stations were operating in the shadows of the mountains.

Dog sledges were by far the best way to navigate the hostile terrain, not least of all because they could carry tents and several weeks’ worth of food supplies, ammunition and sacks of coal for the huts.

There was a savage beauty to the land but travel was both arduous and hazardous. Direct routes often took a path across the sea ice. When doing this, Greenland dogs were often harnessed differently to the way we see Huskies hitched in other parts of the world.

Instead of the usual train hitch—pairs of dogs running one behind the other - Greenland dogs were often arranged in a fan hitch. It spread their weight and, if the ice thinned and cracked at any point, only one or two dogs might fall through before the sledge could be stopped. In train formation, the entire team could be dragged into the watery void; sledge and driver swallowed with them.

Of equal importance to their role in transport was the dogs role in detection. They are constantly alert to any unusual or threatening scents, and able to pick them up from as far away as three miles, depending on the wind. These may be the distant peril of a prowling polar bear or the whiff of humans hiding in a far-off hut. A good dog man knew how to interpret their signals.

Eske Brun was aware that as ‘armed civilians’, his patrolmen were not covered by the Geneva Convention. If caught, the enemy might execute them as spies rather than take them prisoners of war. It was not practical to put them in standard uniform. However Governor Brun appointed them to military ranks and issued them with armbands to identify them as military personnel. That status was boosted when they were also made a reserve unit of the U.S. Army.

Crusted with ice, armbands were hard to see and the frozen fabric had a tendency to snap and fall off. It was common for the Sledge Patrol to keep an armband in their pocket, only putting it on when approaching a German Position.

FIRST CONTACT

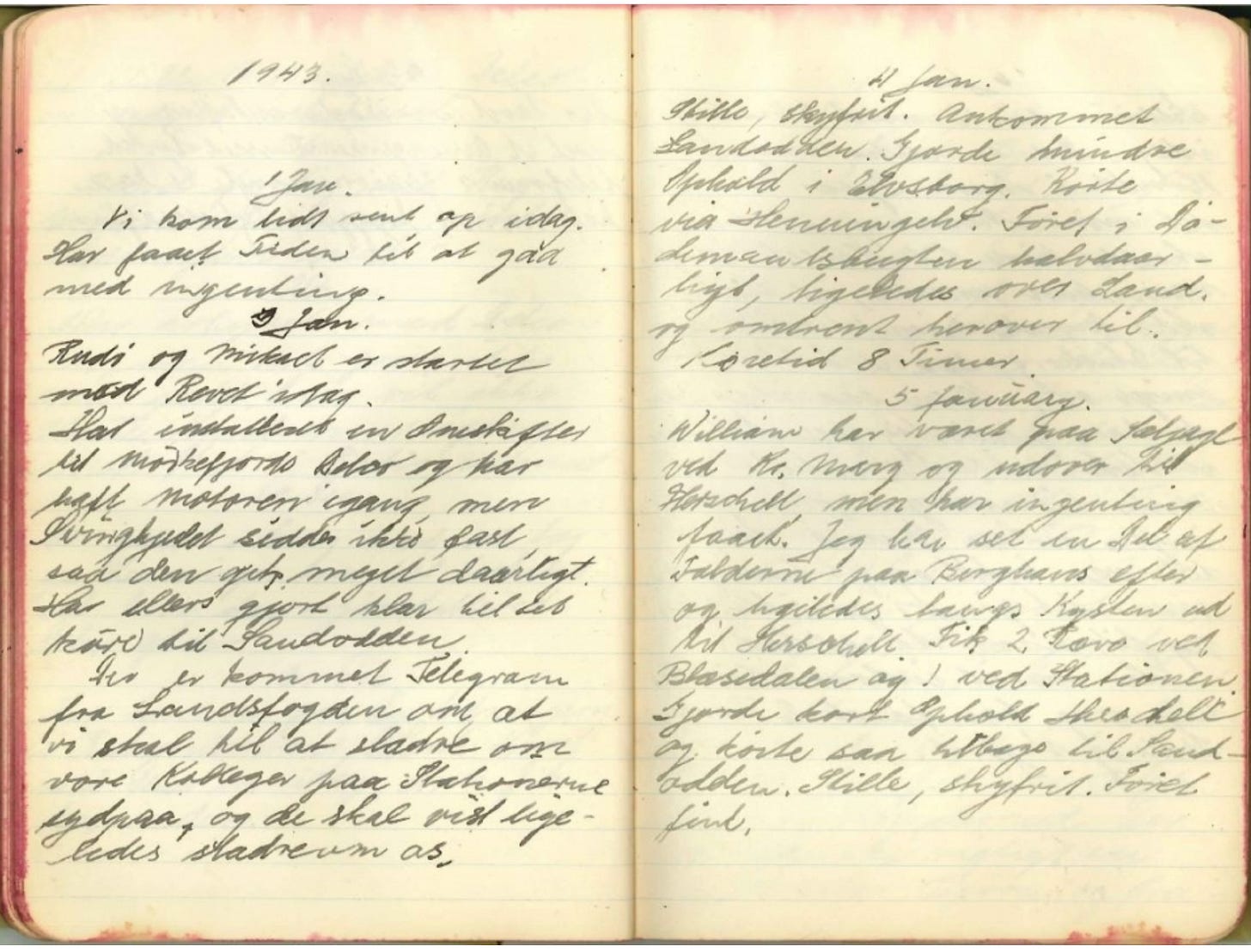

March 8, 1943:

Marius Jensen and two Greenlandic patrol members, Mikael Kunak and William Arke, set out to patrol the area north of Eskimonæs, their home base. There was a trapper’s hut on Sabine Island, 60 miles (96 km) away, that they wanted to check.

The dogs picked up the scent of ‘strangers’ from several miles away - aromas of different tobacco and food items. Their ears pricked up and their pace changed, signaling that something ‘un-Arctic’ was ahead. As they drew nearer, they saw smoke coming from the chimney and footprints on the ice: the footprints of men wearing military-style boots with heels, not the soft sealskin kamiks worn by local trappers.

However before they reached the hut, they saw two men escape up the mountainside. Inside they found two half-empty mugs of coffee on the table, sleeping bags, Nazi uniforms, daggers, supplies, coal and almost half a polar bear.

The three men set out straightaway on the return journey to Eskimonæs, to report the discovery as soon as possible, but Jensen knew that the dogs were in need of rest and so they stopped for the night in a hut just 5 miles (8km) south of Sabine Island.

Meanwhile the two German soldiers had made it quickly back to their headquarters at Hansa Bugt, a secluded inlet that was also on Sabine Island. Jensen and his men had found a hut with two scouts, not realizing that over the hill was Germany’s secret headquarters, commanded by Lieutenant Hermann Ritter.

March 11, 1943:

Sheltered in the tiny hut, they heard men approaching during the night. The dogs had raised the alarm. They had no idea how many men, or the extent of the threat, but made the decision to escape immediately on foot, grabbing only their rifles.

Ritter had sent a patrol to find them, hoping to stop them before they could report their sighting of the German presence to the Sledge Patrol headquarters at Eskimonæs. Their orders were to bring them back - alive or, if necessary, dead.

March 13, 1943:

Fortunately, after their narrow escape, Marius Jensen and his men did make it back. They had slogged nearly 100 miles across ice and snow in two days.

Summing up the setback, Kurt Olsen, a senior member of the Sledge Patrol based at Eskimonæs , managed to radio the following message to Governor Eske Brun in Nuuk:

“We have suffered a severe loss. Half of our dogs and three fully equipped sledges. Fritz also got his hands on Marius’s journal, so he could not be better informed of our whereabouts.”

RAID

March 23, 1943:

Ten days later, in the early evening, the Sledge Patrol’s command base at Eskimonæs was attacked. Lt. Ritter had sent a squad with submachine guns, as well as rifles and revolvers. It was a carefully planned assault.

Compared to the simple trapper’s huts on the trails, the station at Eskimonæs was luxurious. The red-painted house had a large living area in the centre with a roaring stove, comfortable chairs and tables. This was ringed with six bedrooms and radio room, together with a generator room. Surrounding the exterior wall of each were storerooms, doubling as outer layers of insulation.

When the Germans arrived, there were only five men at the base. Days earlier, some had been sent to the radio station at Ella Island, whilst Marius Jensen and Eli Knudsen had been despatched north to look for another patrolman, Peter Nielsen, who they thought did not yet know of the German presence.

On hearing their approach (those brilliant dogs again!) the camp commander, Ib Poulsen, stepped out - his rifle loaded - to ask the Germans what they wanted. After some initial distantly shouted exchanges, the Germans inquired:

“Do you intend to offer armed resistance?”

Poulsen responded succinctly:

“Jawohl” (“Yes”)

The Germans opened fire! Somehow, in the hail of bullets that ensued, Poulsen managed to escape. He ran into the cold night, without his arctic-weather gear, save for his trousers and sealskin boots. Miraculously he survived. At a hidden supply mound he found a tent, which he cut into a makeshift anorak and then walked 230 miles to Ella Island. The others also escaped, faring better because they had a moment to grab their polar clothing.

The base at Eskimonæs did not survive. The Germans torched it and in a spectacular, crackling blaze against the snow, it burned to the ground.

AMBUSH

Meanwhile Marius Jensen and Eli Knudsen had found Peter Nielsen and the three were now travelling back to Eskimonæs. Eli Knudsen had the better dog team and had pulled far ahead of the others. He headed for Sandodden hunting station to get some rest.

March 26, 1943:

After the raid on Eskimonæs, Ritter’s patrol had also headed to Sanodden. When Eli Knudsen arrived they were lying in wait.

As the soldiers rose, like apparitions, from the snow, Eli mushed his team to make a run for it. Ritter ordered his men to ‘shoot the dogs’. Several fell in the first burst, dragging as the sledge continued. Then in the second burst, Eli Knudsen was shot and killed.

It was unintended; the gunner’s aim was off because of a jam. Hermann Ritter later recalled that he deeply regretted Knudsen’s death and that he had recurring nightmares about it.

Ritter was an ‘old school’ soldier, doing his duty as best he could, but he had no sympathy for the Nazi cause. Before this command he had at one time been investigated by the Gestapo for some of his remarks. More senior officers, who had regard for him, spoke up and saved him. He was here partly because of his polar expertise and partly to put him out of the way.

The dead dogs were swept under the snow, the rest of the team were staked out and the sledge drawn up outside the hut. The stove was lit.

When Marius Jensen and Peter Nielsen arrived a little later, they expected to see Eli Knudsen inside. Instead they were ambushed by Ritter’s men. Outnumbered and outgunned, they surrendered.

CARDS, CONTEMPLATION AND COMRADESHIP

As prisoners of war, Jensen and Nielsen were taken to Ritter’s HQ at Hansa Bugt on Sabine Island.

With the German location on Greenland having been detected, Ritter assumed it was only a matter of time before U.S. bombers would be called in. His job was to survive and save his men, until the sea-ice melted enough for a rescue ship to dock and evacuate them.

To that end he launched a campaign of reconnaissance to seek out places to hide and to find and destroy any Allied communications centres.

He recognized that Marius Jensen not only had innate knowledge of the topography, he was also something of a dog whisperer with the oftentimes quarrelsome Greenland dogs. Their power and pull was unmatched but they were aggressive and independent, requiring expert handling - something many of his men struggled with.

Jensen and Nielsen were unshackled and unguarded, having given their word not to escape. In the evenings, Ritter and Jensen played cards, discussed philosophy and shared their mutual passion for the Arctic. They formed a friendship and deep regard for each other, despite also retaining their sense of patriotic duty.

Marius Jensen was even able to persuade Ritter to let Peter Nielsen take a sledge back to Sandodden to buttress Eli Knudsen’s grave, protecting his corpse from scavengers like arctic foxes. In exchange, he agreed to co-operate, to show Ritter the routes and to drive his sledge.

This takes us to that stage of the story where we started, at the Myggebugten hut on the morning of April 19th; with Ritter staring down the barrel of his own rifle and Jensen saying:

“Now you are my prisoner”

This followed, if you remember, Lt. Ritter sending a squad of soldiers to destroy the radio station at Ella Island

THE RACE FOR ELLA ISLAND

Jensen feared that the German soldiers Ritter had sent to Ella Island would kill the personnel there. Consequently, he left Ritter in the hut and set off alone, determined to beat them and to warn the Danish radio crew.

At 31-years-old, Jensen was in his physical prime and the arctic wilderness was his natural habitat. He was deeply bonded with his crack dog team and he had given the Germans a map that followed circuitous trails around the fjords. He knew a shorter route across the ice!

To make his sledge lighter, he unloaded a large amount of the supplies and left them in the hut with Ritter. There was no need to bind his prisoner; he was confident that he would not escape.

Ritter, assuming that Jensen had headed off to his own safety, had no choice but to stay where he was, and await the return of his patrol. It, at least, afforded him an opportunity to rest and restore his strength a little; something that he would all too soon be required to draw upon.

Greenland was sparsely populated by humans but it had a sizeable population of polar bears and musk oxen. To have ventured far from the hut would have been suicide.

April is calving season for musk oxen—a month when the bulls are even more protective and aggressive than usual. If a bull senses danger, it will charge. That is 600 lbs (270 kgs) of bone and muscle, armed with a dense plate of horn across the forehead, together with powerful hooking horns hurtling at you with no sense of mercy. These meat juggernauts can reach speeds of 25–30 mph (40–50 km/h) with terrifying acceleration from a standing start.

Matadorial agility is limited when swaddled in thick polar gear and avoidance nigh impossible. Without his rifle, Ritter would not have stood a chance against a musk ox. Similarly, it would have been fatal to venture unarmed into polar bear country. Polar bears were by far the most dangerous animals out there and they can sprint at 40 mph (64.4 km/h).

Marius Jensen arrived at Ella Island before the Germans but found that the crew there had already evacuated to Scoresby Sound. This was the southernmost terminus for the Sledge Patrol and a key radio station. It was also an administrative base, where the local official, Poul Hansen, still flew the Danish flag over government buildings and a safe harbour, where the US Coast established their Greenlandic foothold.

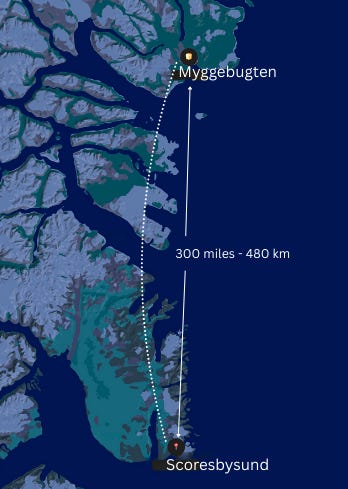

Scoresby Sound was south of Ella Island. Myggebugten was north. In his report Governor Brun noted:

“The obvious thing under these circumstances would be to continue directly to Scoresby Sound. But as Corporal Jensen thought it would be inappropriate to arrive empty-handed, he first sledged 150km back to Myggebugten…”

That is a journey of between 5 and 7 days, depending on the weather.

A POLAR BEAR WITH A GUN

April 30, 1943:

A week of waiting alone in the arctic silence, broken only by screeching winds, even to a seasoned hunter like Ritter, must have been agonizing. Would his patrol return? Would Jensen return? Would anyone find him before supplies were exhausted?

Finally, late one morning, he heard dogs outside. For a moment, a deep breath of relief stilled his mind. He went to the door. Head bowed to shield from the blinding light outside, he heard the familiar click-clack of a bolt-action rifle chambering a round. Upon opening the door he was confronted, not by one of his men, but by the surreal and menacing sight of a polar bear with a gun.

This fleeting mirage was in fact Marius Jensen. As well as holding Ritter’s rifle, he was wearing the standard kit of the Sledge Patrol – polar bear trousers.

Polar bear hair is hollow, buoyant and warm. More importantly, it is naturally water-repellent. So if a patrolman were to fall through the ice, it wouldn’t soak up water as fast as wool; potentially saving him from immediate hypothermia.

It was a sight that must have been at once terrifying and comforting. In many ways the men had become friends, valuing the ‘code of the arctic’ above the laws of nations. Ritter must have realized that Jensen had ‘come back for him’, as much to save him from certain death as he had to deliver him as a prisoner of war.

THE LONG MUSH TO ALLIED HQ

May 1, 1943:

After only a single night’s rest, Jensen loaded the sledge with all supplies then; with his captive at gunpoint, set out on the 300-mile (480 km) trek south to Allied HQ at Scoresbysund - a journey that required astonishing physical and mental endurance.

Marius Jensen rode the runners of the sledge. Hermann Ritter - the walking prisoner - was obliged to keep up on skis. To prevent the sledge from being bogged down in soft snow, Ritter often had to break trail in front of the dogs, or push the heavy cargo from behind.

Sledges only work on compacted snow or ice - the trappers’ trails - but if it veered into a drift at the side of a trail it had to be bumped and levered to set it back on the trail. Manhandling a heavy sledge on harsh sliding terrain was strenuous, grinding labour.

The great enemy of effort in the arctic is sweat. When you sweat, moisture fills the warm air pockets created by the insulation of furs. As soon as you stop to rest, your body temperature drops, and that moisture freezes into a layer of ice against your skin, risking fatal hypothermia.

Polar travelers move with a deliberate, slow trudge, constantly monitoring their exertion to ensure they don’t break a sweat. If they feel themselves getting too warm, they vent their clothing (opening collars or cuffs) to let the heat escape before it turns into moisture.

Both men had oilskin anoraks that worked well for this. Their hoods were lined with wolverine fur - the only fur that doesn’t hold frost from your breath; you can just brush the ice crystals away.

We don’t know the exact route they took, but clearly there were a lot of fjords to cross. For much of the year these are frozen safely solid, but in May, when they were travelling, it was beginning to become treacherous. A layer of ice might look two feet thick and perfectly white, but could be honeycombed with internal melt-channels. This is known as rotten ice.

Marius needed all his skill to navigate the best route; to keep the journey as short as possible, but also to avoid rotten ice, and in addition, to take advantage of the trapper’s huts on solid ground for overnight stops. Overnighting on the ice could only be done with a tent.

A trapper’s hut was typically no more than ten feet square and there was no separate room for a prisoner. Sleep was obviously essential, but could Jensen trust Ritter not to turn the tables once more?

These two rugged outdoorsmen had found a common bond, but the fact remained that their countries were at war, and Ritter was a prisoner of war on his way to be handed over to the enemy authorities. It was conceivable that Ritter could take the rifle, while Jensen slept and force him to turn back for the German base on Sabine Island.

At night Jensen put the rifle’s bolt in a bag tied to his body.

Despite this precaution, their mutual dependence on survival triumphed over any suspicions. Hermann Ritter was unlikely to kill the only man who knew how to navigate the dog team back to safety. He had done his duty, as he saw it, but was privately glad for a way out of a war he disapproved of.

For Jensen and Ritter, their world was an endless horizon of frozen white, prismed only by the coruscating frost on their goggles, but there was another world outside their solitary existence - a world at war. There were still German troops at Hansa Bugt on Sabine Island, and they were still operating the radio station there.

SABINE ISLAND IN FLAMES

May 14, 15 1943:

Alerted to their presence there by Marius Jensen’s initial discovery, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) launched a long-range bombing mission from their base in Iceland. A flight of bombers strafed the buildings and dropped bombs, leaving the station in flames.

ARRIVAL

May 22, 1943:

Three weeks after setting out, with his dogs almost dropping in their harnesses, an utterly wearied Marius Jensen pulled in to the Allied-controlled station at Scoresbysund. Even more drained and spent was Lt. Hermann Ritter.

Jensen handed over his captive to the U.S. authorities. It was a bittersweet moment; both a release and a strange way to bid farewell to a comrade with whom he’d shared so much adversity.

Ritter reportedly asked only for a bath and a long, undisturbed sleep; both requests were granted. At last, for him, the war was over.

He was taken to the United States, where he spent the rest of the war at Camp Clinton in Mississippi. He was well treated. For a man who had spent so much of his life in the frozen, desolation of the Arctic, the humid heat of Mississippi must have felt like another - and very strange - planet.

AFTER THE WAR

In 1945, Hermann Ritter returned to Austria, where he lived the remainder of his life with his wife. Although he avoided the limelight, he always spoke of Marius Jensen with profound admiration. He viewed him not as an enemy who defeated him, but as a fellow man of the ice who had saved his life by taking him prisoner. Hermann Ritter died in 1968 at the age of 76.

After the war, Marius Jensen remained in Greenland, working as a trapper for a few more seasons, but eventually returned to Denmark. He died there in 1991, at the age of 80. For his wartime services, he was awarded the US Legion of Merit Medal and the King Christian X Liberty Medal from his native Denmark.

LEGACY

The Greenland Sledge Patrol was disbanded at the end of the war, but re-established in 1950, under the dark clouds of the ‘Cold War’ with the Soviet Union. It continues to this day as an elite unit of the Danish Navy, though under a different name. They still use dog sledges (rather than snowmobiles) to patrol because dogs have greater ‘mechanical’ reliability and their early warning capabilities against polar bears are unmatched. Today they are called the Sirius Sledge Patrol (Slædepatruljen Sirius) - a nod to the common nickname of Sirius - ‘The Dog Star’.

Frederik X, the current King of Denmark, served in the Sirius Patrol, when he was Crown Prince during the early 2000s. During that time he once completed 2,200-mile trek through Northern Greenland.

However, perhaps the greatest legacy of this story is that, although cruel Fate can throw good people on different sides in a conflict, they do not need to hate. Honour and respect remain vital kindling for the warm fire of friendship.

The words ‘sledge’ and ‘sled’ are to some extent interchangeable. Although sled is used universally in US English, sledge is more widely used in UK English. However there is also a functional distinction. A sled is more of a lightweight transport for a single person or for recreation. Whereas a sledge is larger and sturdier, intended for carrying cargo, supplies, or equipment.

Although Greenland is the world’s largest island, it is nowhere near as massive as it looks on a map. Maps today follow the map projections made by Gerardus Mercator in 1569. These preserve crucial angles and shapes that are essential to navigation, but they cause a visual distortion towards the poles, because of the way the globe curves and tapers. On a map Greenland appears to be fourteen times larger than it is.

If you enjoyed this tale, you might also like:

JACK - THE DOG WHO SAVED A BATTALION

SECRETS OF THE WORLD'S FIRST MILITARY DOGS

Wow, what an incredible story. Worthy of a major movie or mini series. We need to be reminded of how much character matters.